The First American “Egypt” Was in the Ohio Valley

📜 The First American “Egypt” Was in the Ohio Valley In the 1700s and 1800s, explorers and settlers described the Ohio–Kentucky–Tennessee valley as “Egypt” because of its fertile floodplains and mound cities that echoed the Nile. Maps still show towns named **Cairo, Memphis, Thebes, and Helena**, proof of this deliberate connection. Like the Nile, the Mississippi and Ohio rivers created a breadbasket of abundance. This truth, preserved in archives and old maps, shows that America’s heartland was once recognized as its own sacred Egypt.

12/4/20254 min read

.🗝️ Hidden Record: The First American “Egypt” Was in the Ohio Valley

Introduction

Most of us are taught to think of Egypt as a faraway land—deserts along the Nile, pyramids rising from golden sand, and temples echoing with the memory of the pharaohs. Egypt is framed as distant, ancient, and disconnected from American soil.

But early explorers and settlers in the 1700s and 1800s saw something strikingly different. Traveling through the Ohio–Kentucky–Tennessee valley, they often referred to this region as “Egypt.” This was not a casual nickname. It was an acknowledgment of the uncanny parallels they observed: fertile floodplains, mighty rivers that flooded and renewed the soil, and great earthen monuments rising from the land—features that mirrored the Nile Valley itself.

To the Native nations, this land had long been sacred, abundant, and central to life. To settlers steeped in biblical imagery, it carried the unmistakable aura of Joseph’s Egypt—the land of grain and provision, a place where people survived famine. And so, the Ohio Valley became known as the first American “Egypt.”

The Abundance of the Valley

The Ohio and Mississippi rivers created some of the most fertile land in North America. Each year, floods deposited rich black soil, leaving fields that yielded bountiful crops of corn, beans, and squash. This rhythm mirrored the Nile’s annual inundation, which for thousands of years sustained Egyptian civilization.

Settlers and explorers were astonished at the productivity of the soil. By the early 1800s, as northern Illinois faced harsh winters and failed crops, families would travel south into this fertile zone to buy grain. Just as the Bible tells of Joseph storing wheat in Egypt to save surrounding nations, these American settlers turned to their own “Egypt” in times of scarcity.

The land became a breadbasket of the young United States. And with it, the name stuck: “Little Egypt.”

The Names That Tell the Story

If there is any doubt about this truth, the maps themselves bear witness. Look closely at 19th-century county maps, and you will see echoes of the Nile across the Midwest and South.

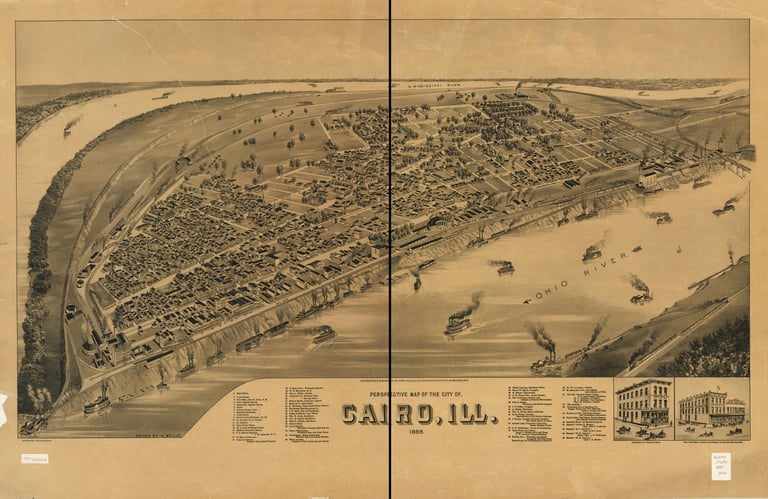

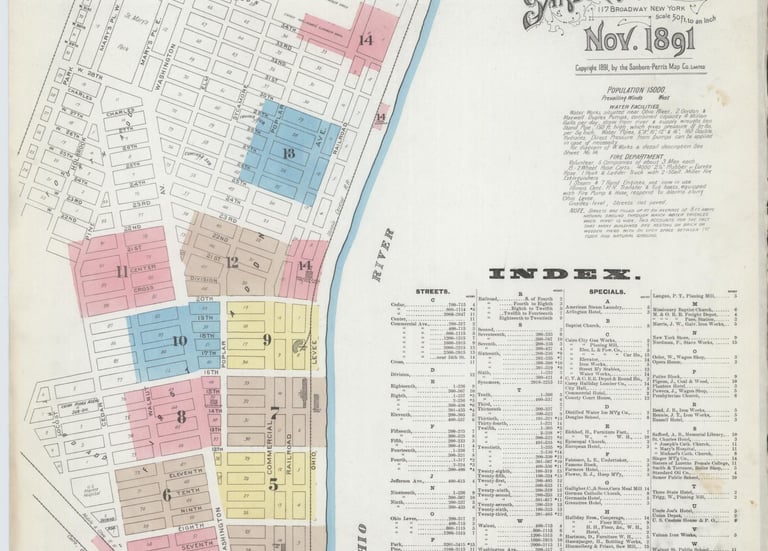

Cairo, Illinois: At the very confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi rivers, this city was named for Cairo, Egypt, where the Nile divides into its great delta.

Memphis, Tennessee: Founded on a bluff above the Mississippi, Memphis was deliberately named after the ancient Egyptian capital.

Thebes, Illinois: A smaller town, but named after the sacred Egyptian city of temples—Luxor and Karnak—once the spiritual heart of the Nile.

Helena, Arkansas: Another deliberate echo of Old World geography in the New.

These were not whimsical choices. They were intentional declarations by settlers who recognized that they were living in a parallel to Egypt.

The maps are still available today in the Library of Congress archives. An 1839 map of Illinois clearly labels Cairo and Thebes. Tennessee gazetteers from the 1850s list Memphis proudly. These documents are verifiable records, preserved for anyone willing to look beyond the surface.

The Pyramids of Earth

The comparisons went beyond rivers and agriculture. Indigenous civilizations of the Ohio and Mississippi valleys had constructed monumental architecture that settlers could not ignore.

At Cahokia, near modern St. Louis, rose Monks Mound—the largest earthen pyramid in North America. Covering 14 acres at its base and standing nearly 100 feet high, it rivaled the pyramids of Giza in sheer mass. Archaeologists estimate it required over 20 million basket-loads of soil to build.

To the settlers of the 1800s, these structures were undeniable reminders of Egypt’s pyramids. Travelers wrote of the mounds with awe, noting their alignments to celestial events, their plazas, and their scale. To them, it confirmed that this land was indeed an Egypt of its own.

For Native nations, these mounds were sacred centers—places of emergence, ceremony, and star knowledge. Though colonial scholars reduced them to “myths,” Indigenous oral traditions hold that they were temples of renewal, aligned to the rhythms of the cosmos. In this way, the American pyramids paralleled the Egyptian ones not only in form but also in purpose.

The Biblical Connection

For settlers steeped in the King James Bible, the comparison was unavoidable. Egypt in scripture was both a place of bondage and a land of salvation. It was where Joseph stored grain and where nations turned in times of hunger.

To call the Ohio Valley “Egypt” was to acknowledge its role as a provider in lean years. The famine relief journeys of the 1830s sealed the association. Newspapers and local histories of the time describe settlers traveling south to gather food, just as Joseph’s brothers had traveled to Egypt for survival.

Thus, the biblical overlay strengthened the name “Egypt” until it became part of the identity of the region.

Why This Truth Was Buried

So why do so few people know about this American Egypt today?

Erasure of Indigenous achievement: Early 20th-century scholars dismissed the mounds as “primitive” or claimed they were built by a “lost race,” unwilling to acknowledge the genius of Native civilizations.

National mythology: America wanted to portray itself as a fresh start, a land without ancient roots. To admit a parallel to Egypt was to admit that this continent already held civilizations equal to the Old World.

Educational silence: Over time, the names Cairo, Memphis, and Thebes became ordinary. Schoolbooks stopped explaining why they were chosen. The deeper memory was cut off.

And so, while the road signs remain, the meaning has been stripped away.

Records You Can Check

For those who want to verify this hidden record, the sources are clear:

Library of Congress Digital Maps: Search for Cairo, Illinois, and Thebes, Illinois, on 19th-century maps.

Illinois State Historical Society: Documents detailing the “Little Egypt” nickname and the famine relief of the 1830s.

Tennessee Gazetteers (1850s): Records confirming Memphis’s Egyptian naming.

Cahokia Mounds UNESCO Reports: Archaeological evidence of North America’s largest pyramid.

19th-Century Newspapers: References to the Ohio Valley as the “Egypt of the West.”

These are not rumors. They are preserved facts.

Why Remembering Matters

To rediscover the American Egypt is to reclaim truth. It reminds us that this land was never empty wilderness. It was already a center of abundance, architecture, and sacred meaning.

It restores dignity to the Indigenous mound builders, whose achievements rival those of the Nile.

It reframes America’s history, showing that its foundations are not just European imports but also global echoes.

And it calls us to remembrance—that Egypt was not only across the sea but also here, under our feet.

Conclusion: The Witness of the Maps

Today, road signs still point to Cairo, Memphis, and Thebes. The maps still carry the names. The mounds still rise from the plains.

The first American Egypt is not hidden in myth. It is preserved in cartography, in archives, and in the soil itself.

The Ohio–Kentucky–Tennessee valley was, and remains, a mirror of the Nile. A place of abundance. A land of pyramids. A living Egypt across the ocean.