The Federal Writers’ Project Preserved Testimonies of Enslaved People

This article explores how the 1930s Federal Writers’ Project preserved over 2,300 first-person testimonies from formerly enslaved people, creating one of the most important archival collections on American slavery. It also examines the overlooked context of these interviews—often conducted under racial power dynamics—and points readers to the Library of Congress and WPA records where the original documents can still be accessed and verified.

2/16/20262 min read

The Federal Writers’ Project Preserved Testimonies of Enslaved People

In the depths of the Great Depression, the U.S. government launched an ambitious employment initiative known as the Federal Writers’ Project (FWP), a branch of the Works Progress Administration (WPA). While its primary goal was to provide jobs to writers, teachers, and researchers, one of its most enduring legacies became the preservation of memory itself.

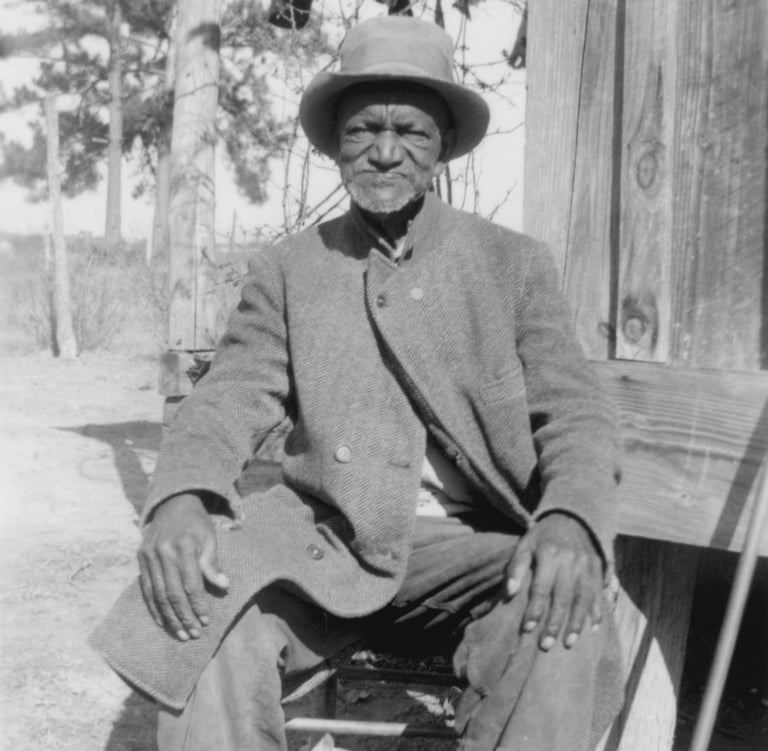

Between 1936 and 1938, FWP interviewers traveled across the American South and parts of the Midwest to record the recollections of formerly enslaved men and women. More than 2,300 first-person narratives were collected, along with hundreds of photographs. These interviews captured stories of daily life under slavery—family separations, labor conditions, resistance, survival, faith, and emancipation. For many participants, this was the only time their experiences were formally documented.

Today, these testimonies are housed in the Library of Congress Slave Narrative Collection, where they remain publicly accessible. The transcripts, photographs, and related documents form one of the most important primary source collections on American slavery.

However, the project was not without complications.

A critical detail—preserved in field notes and internal correspondence—is that many interviews were conducted in racially segregated environments. In numerous cases, formerly enslaved interviewees spoke to white interviewers, sometimes in the presence of white supervisors or within communities where racial power structures were still firmly intact. Letters between project administrators reveal concerns about interviewer bias, dialect transcription, and whether participants felt fully safe to speak openly.

Some narratives reflect this tension. Certain interviewees described former enslavers in restrained or softened terms, while others offered more direct accounts of brutality. Historians have long noted that context matters: speaking honestly about enslavement in the Jim Crow South required courage.

Despite these limitations, the collection remains invaluable. Cross-referencing WPA narratives with plantation records, Freedmen’s Bureau files, and Civil War–era documents has confirmed many of the accounts’ historical accuracy. The narratives also preserve details rarely found in official records—songs, foodways, folklore, naming practices, and personal reflections that government ledgers never recorded.

The Federal Writers’ Project did not create these stories; it preserved them. And though shaped by the era in which they were recorded, the testimonies remain a powerful archival bridge between slavery and modern America.

The proof endures in ink and paper: WPA transcripts, correspondence, and archival collections that continue to be studied, cited, and reexamined today.