Paper Walls: How Federal Employment and Municipal Planning Enforced Racial Inequality

This post examines how racial inequality in the United States was systematically enforced through official records rather than overt violence alone. By analyzing federal employment files and municipal planning and zoning documents, it reveals how segregation, job exclusion, and neighborhood destruction were quietly implemented through policy and paperwork. Grounded in archival evidence, Paper Walls shows how discrimination was designed, documented, and preserved within government systems whose records still

1/27/20261 min read

Paper Walls: How Federal Employment and Municipal Planning Enforced Racial Inequality

Throughout the 20th century, racial inequality in the United States was not maintained solely through violence or social custom—it was administered through paperwork. Two of the most powerful tools were federal employment systems and municipal planning and zoning files, both of which left extensive documentary trails that can still be examined today.

Federal employment and agency records reveal that many government institutions quietly enforced racial hierarchy. Agencies such as the U.S. Postal Service, Civil Service Commission, and various New Deal–era programs maintained segregated workspaces, limited promotion opportunities, and assigned Black workers to the most dangerous or lowest-paid roles. These practices were often justified as “local discretion” and recorded in personnel files, internal memos, and union agreements—documents now housed in the National Archives.

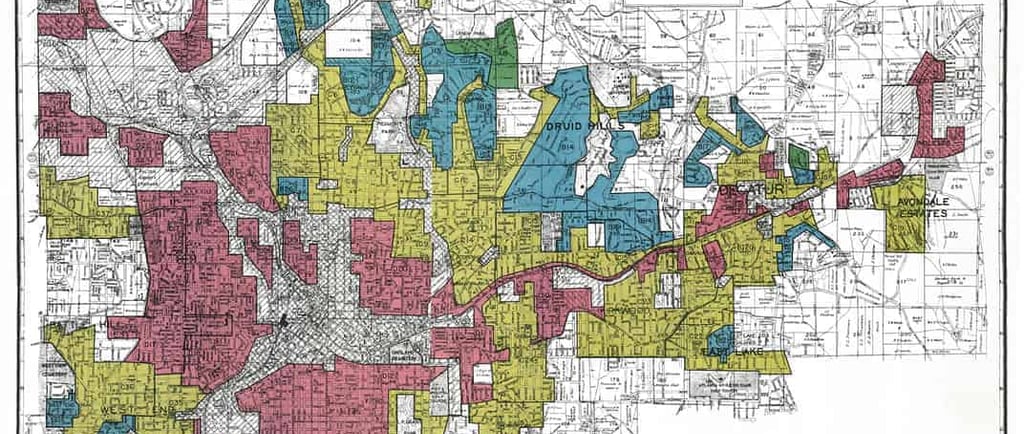

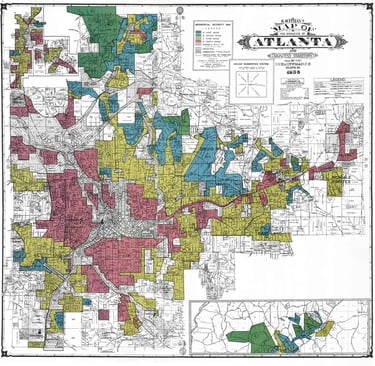

At the city level, municipal planning and zoning files were used to reshape neighborhoods along racial lines. Urban renewal plans, highway construction maps, and zoning ordinances show that Black neighborhoods were frequently labeled “blighted” and targeted for demolition. Highways, civic centers, and industrial zones were routed directly through thriving Black communities, displacing residents and erasing generational wealth. Planning commission minutes and redevelopment maps confirm these decisions were deliberate, not incidental.

Together, these records expose a system where inequality was enforced not only by prejudice, but by policy. The evidence remains in federal archives, city halls, and planning offices—quiet proof that discrimination was designed, approved, and filed away.