Hopewell Earthworks

Geometry Beneath the Fields

12/31/20252 min read

Hopewell Earthworks — Geometry Beneath the Fields

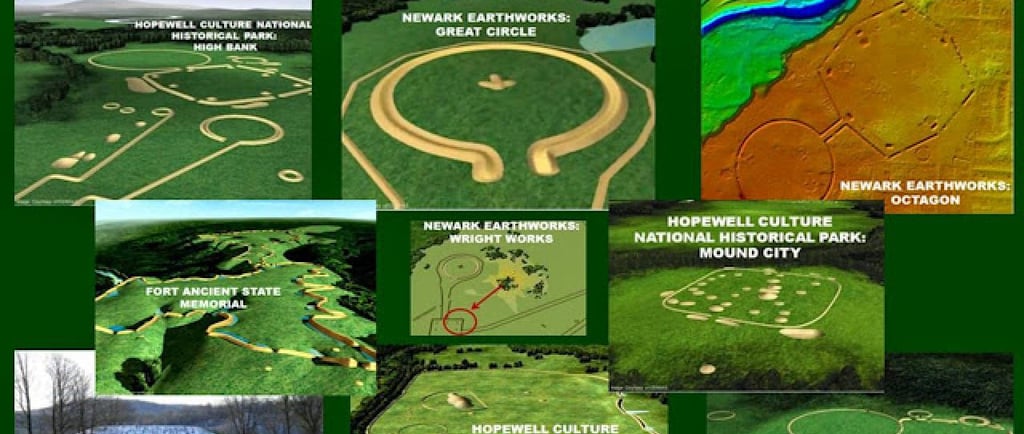

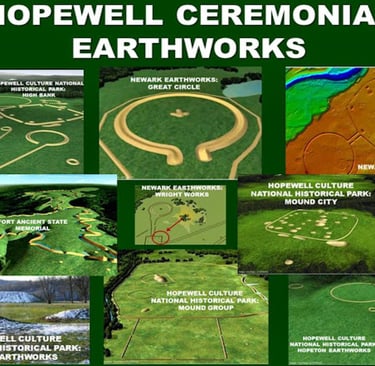

The area now preserved as Hopewell Culture National Historical Park represents only a small remnant of one of the most extensive ancient earthwork landscapes in North America. Between roughly 100 BCE and 500 CE, Indigenous peoples associated with what archaeologists label the Hopewell tradition constructed hundreds of large-scale geometric earthworks across present-day Ohio and neighboring states.

These earthworks included enormous circles, squares, octagons, and parallel-walled avenues, some enclosing hundreds of acres. Modern research has confirmed that many of these structures were built with remarkable mathematical precision and astronomical alignment, including connections to the Moon’s 18.6-year cycle. This level of planning required advanced knowledge of geometry, astronomy, surveying, and coordinated labor.

By the time European-American settlement accelerated in the 19th century, much of this landscape was already under threat. As farmland expanded, earthworks were systematically plowed down, filled in, or dismantled. Fertile soil deposits associated with the earthworks made these sites especially attractive for agriculture. In many cases, farmers viewed the mounds and embankments as obstacles rather than cultural heritage.

Early maps and survey records from the 1800s document earthworks that no longer exist today. In some counties, more than 90 percent of known sites were destroyed before formal archaeological study could take place. Unlike stone monuments, earthen architecture proved especially vulnerable to repeated plowing and land leveling.

The areas now protected within Hopewell Culture National Historical Park—such as the Mound City Group and the Newark Earthworks—survive largely because they were set aside before total destruction occurred. Even so, parts of the Newark complex were incorporated into later developments, including roadways and a golf course, illustrating how preservation often came only after significant loss.

The disappearance of most Hopewell earthworks contributed to long-standing misconceptions that Indigenous societies in the region were small, scattered, or technologically simple. In reality, the scale of construction and regional coordination indicates complex social organization and ceremonial systems spanning hundreds of miles.

The hidden record beneath Ohio’s farmland tells a different story: one of intentional design, scientific observation, and monumental landscape engineering. Recognizing what was erased is essential to understanding the true depth of Indigenous history in North America and restoring visibility to civilizations long treated as invisible.